The embrace of childish things and vice versa

On the way to the grocery store the other day with my middle child, we were listening to an audiobook, and the choice of the day was a teleplay of Matilda, by Roald Dahl. Not an exact reading but rather a dramatized radio play of the book, it elaborated some of the scenes, especially those in which the librarian is first interacting with Matilda in her long days reading at the public library while her mother sat playing bingo in a nearby town. When Matilda first started going to the library, she set upon the children’s section, and upon conquering all of those books (including, I gathered, all the chapter books and adolescent lit), she asked the librarian if she could recommend a good adult book. The librarian, amazed at this precocious child, gave her Great Expectations to start with. She then went through the rest of Dickens, Austin, Steinbeck, and Hemingway. Upon reading Hemingway, Matilda recounts to the librarian how much she likes the novels, but doesn’t quite understand all the bits about the men and women, to which the librarian responds (in essence), “Don’t worry about what you don’t understand, just let the words wash over you.” Helpful advice. I had to just chuckle at this part of the drama, as I find myself constantly thinking about how appropriate certain books are for my eleven-year-old to read, and I found it so refreshing to hear an adult muse rather thoughtfully about a young child’s reaction to Hemingway’s more salty prose rather than respond with panic that she may have encountered something that was inappropriate. Now it strikes me that Roald Dahl, like Maurice Sendak, Enid Blyton, JK Rowling, and a number of other writers of “children’s lit” give their young charges way more agency than we give many of our teenagers this day and age, but it does give you something to chew on. What I love most about this part of Matilda is how it takes a children’s book to tell us that children can actually read and love — if not completely understand — “adult” literature and, more importantly, should at least be allowed to read it and read it with abandon.

Just as I was finishing graduate school with a degree in Comparative Literature in the mid- to late-90s, when I was in my mid twenties, and moving to Chicago to begin my career, I noticed several of my new work colleagues desperately attached to a new series of what I dismissively dubbed as “young adult fiction.” That series was Harry Potter by J.K. Rowling. Everywhere I went, by el train, by bus, I saw people my age reading these books. When the first movie came out in late 2001, everyone clamored after work to grab a drink and then go see it at the nearby cinema. I couldn’t believe it. Why, on earth, would anyone be so interested in kids’ lit? It took me more than 15 years and having children of my own to figure out why.

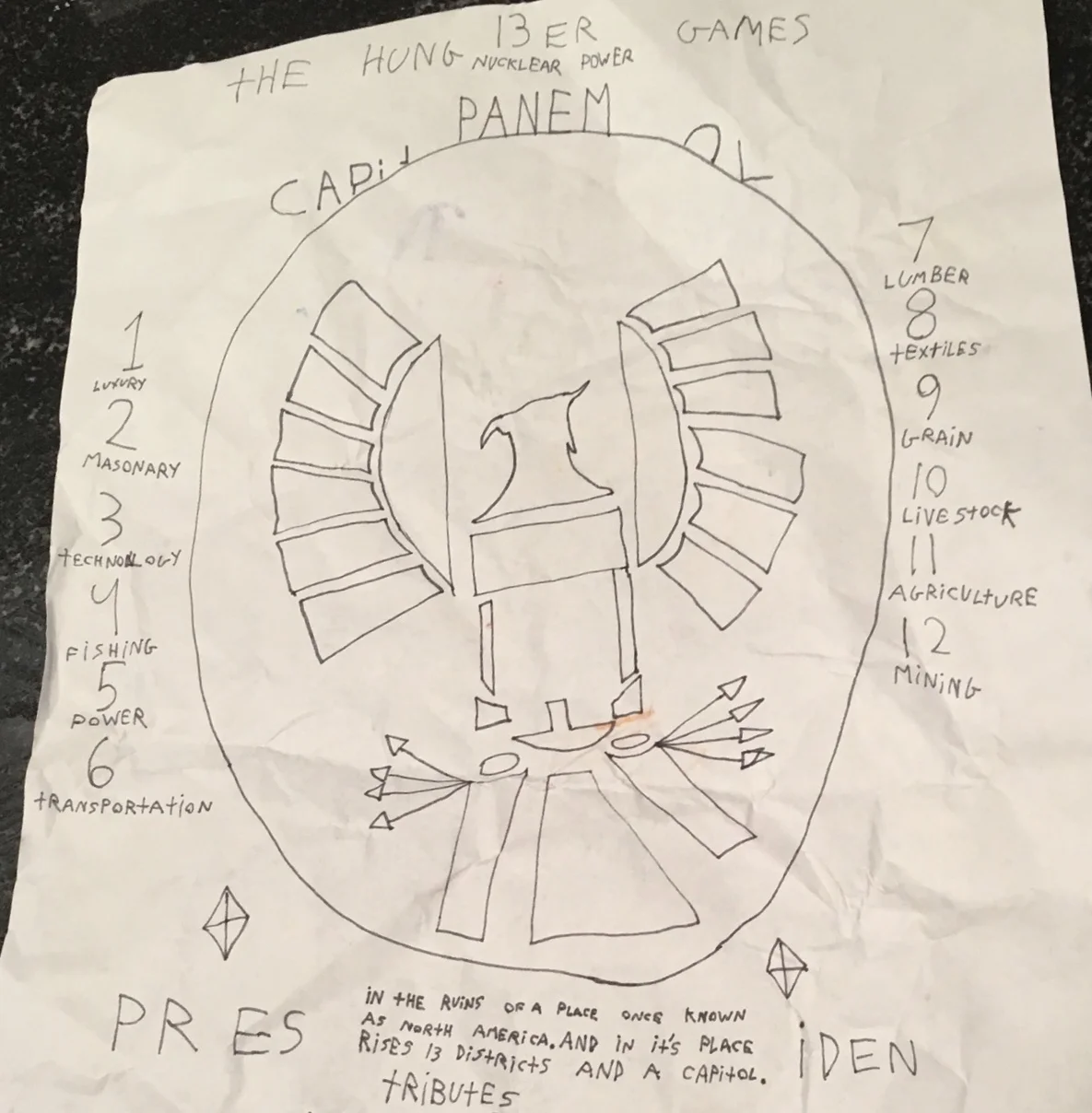

I’ve been listening to this great podcast out of Harvard Divinity School called Ministry of Ideas, and one of their recent episodes, “Child’s Play,”speaks about how we shouldn’t be so dismissive of the popularity of children’s literature among adults. In fact, authors such as Rowling, Phillip Pullman and others have started a revolution of sorts when it comes to children’s literature. They have broken down the divide built steadily from the onset of Henry James’ “Future of the Novel” in 1899, where he asked people to “put away childish things.” In the 19th century, we saw true inventiveness in the writing of Lewis Carroll (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland), J.M. Barrie (Peter Pan), and others. Adults and children alike would read with anticipation and wonder. But it seems as if after WWI, books intended for children became much less challenging, and relegated to the worlds of fantasy and fable without the emotional complexity they once had, and the wall between “adult” and “children’s” fiction became ever harder to transcend. With Harry Potter, just ten years after the fall of another great wall, that barrier seemed to fall dramatically. Prior to 2000, the New York Times bestseller list, published since 1931, had no division between adult and children’s fiction. But after Harry Potter spent a whopping 79 weeks at the top of the fiction list, publishers felt that more “deserving” adult books were being left behind in favor of these children’s books, so a new category of “Children’s Fiction” came into existence. But this division seems to have come a bit too late, as the revolution had already begun. The questions of “where do we come from,” “what is the nature of good and evil,” and others dominate much of children’s and young adult literature. Death had become an ever present theme, and the authors have not shied away from showing death in all of its reality: its pain, suffering, and emotional devastation. In fact, whereas “story” has become less and less obvious in most adult fiction (David Foster Wallace, anyone?), adults and children alike have flocked to Harry Potter books, as well as The Hunger Games and The Golden Compass trilogies to take part in fantasy, yes, but, let’s face it, these books depict a larger psychological realism that only seemed to exist in the realm of adult fiction. There may be a heavy escape quality to children’s lit, but the emotional resonance is palpable. The line between childish things and adult experience is ever blurred.

So, adults now enjoy kids’ books and read them ever more unabashedly. Movies get made that channel our collective memories of all things awesomely retro. And shows like “Stranger Things,” which is all about kids, even though many kids below the age of 12 or 13 are strongly discouraged from watching the show, have captured our imagination and topped the critics charts. Although, interestingly, when I think about engaging in these shows, movies, and books with my own children, one who even calls himself a “tween,” I get some cross-eyed looks from other parents. It is apparently fine to capture this imagination and bottle it for adults, but we’ve become ever more puritanical about exposing our children to so much of this cross-over content. I must say, that my critical and — let’s face it — snotty reaction to Harry Potter back in the day was because I valued the division between adult things and children’s things, even though most of my upbringing involved reading things way ahead of my age in terms of what may have been deemed appropriate now in today’s overly cautious child-rearing climate. I was reading novels about Jewish mysticism, non-fiction works about “unwanted” or oprhaned children, and plays set in apartheid South Africa in junior high. My parents, who heavily censored my television consumption (no “Dukes of Hazard” or “Love Boat” for me), left me virtually and physically unattended when it came to the books I read. I mean, seriously, when you are a child raised with the image of someone being tortured and crucified with nails pounded into flesh being burned into your consciousness every Sunday in children’s church, I think you get a fair idea of the world’s cruelty pretty damn quick. I am sure that much of the content of those early books was above my understanding, but, like the librarian in Matilda suggested, I often just let the words wash over me… words that I would come back to time and time again when the realities of life caught up.

So am I trying to say that kids should just read anything they want? Not entirely. But if the podcast “Child’s Play” did anything for me, it ultimately provoked a deeper question: if we can’t dismiss children’s books from the adult cannon, why should we separate adult books or at least mature ideasfrom children? My oldest child is a precocious reader. And when you mix that with a Montessori school setting with mixed age classes of 4th graders in with 6th graders, you are going to get a fair share of “I want to read what [such and such, two years older than me] is reading.” And so began the discussion of whether or not to read The Hunger Games when Ettu was not quite nine. The Hunger Games inspires strong reactions from parents in terms of its overt violence and the the cruel subjugation of the powerless (both children and adults alike) by those in power. But as I read these novels myself a few years ago, I could not help but think of similar stories or novels I read as an adolescent, namely “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson. This short story, published in 1948 in The New Yorker to the shock of many describes a small town’s annual ritual, which results in the stoning death of one individual by the others (could be one’s own child, mother, brother) to ensure a good harvest, essentially symbolically purging the town of the bad to allow for the good. It’s tradition… it’s what has always been done. Now this story was first published for adults; however, it has become nearly required reading for most middle school kids, like myself in the early 80s. I remember being horrified by the content. A teacher in New Mexico, Lisa Weinbaum, recounts on the site “Teaching Tolerance” how she decided to use this short story after some horrible acts of “play” bullying resulted serious injury in one or more students in her school. Upon reading the story, they reacted, as I did, with a mix of horror and disbelief that this could actually happen. The teacher simply said that this is what is happening every day in the lives of the kids at the school. It happens when we bully others, when we cheer on the bullies, or when we simply turn and walk away, doing nothing. In the days and weeks that followed her teaching of this story she noticed, not uncoincidentally, these bullying games in the bathrooms coming to a stop completely.

In “How Banning Books Marginalized Children,” from the October 1, 2016, issue of The Atlantic, Paul Ringle begins his article with this:

Every year since 1982, an event known as Banned Books Week has brought attention to literary works frequently challenged by parents, schools, and libraries. The books in question sometimes feature scenes of violence or offensive language; sometimes they’re opposed for religious reasons (as in the case of both Harry Potter and the Bible). But one unfortunate outcome is that 52 percent of the books challenged or banned in the last 10 years feature so-called “diverse content” — that is, they explore issues such as race, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation, mental illness, and disability.

When I have had conversations with parents about some of the books my eldest child is reading or wants to read, I often am met with a mix of admiration for his prolific reading but also clearly a little reticence, as the content often conflicts with notions of what might be deemed age-appropriate or too anxiety producing. The content at question often involves a mix of violence, light profanity, sexual undertones (or, let’s face it overtones — not to mention straight out misogyny — in the case of Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels, a current favorite), etc. But it hasn’t escaped me that, as Ringle notes in his article, when we think of how and what children read and what is acceptable, the real question may actually be which children are we talking about. He goes on to say:

Who benefits when Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of Part-Time Indian, which deals with racism, poverty, and disability, is banned for language and “anti-Christian content”? Who’s hurt when Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings’s picture book I Am Jazz, about a transgender girl, is banned? The history of children’s book publishing in America offers insight into the ways in which traditional attitudes about “appropriate” stories often end up marginalizing the lives and experiences of many young readers, rather than protecting them.

When the subjects of slavery or civil rights or Native American genocide or colonialism or war or a host of other themes are barely mentioned in children’s historical picture books, it is important to note that many of the reasons for not bringing these things up for fear of being “emotionally inappropriate” stem from a tradition, established in the 19th century, to serve the needs of the “white, wealthy Protestant producers and consumers… [consumers] who have dominated the field of American children’s literature for much of the past 200 years.” I remember pausing when reading a book on Abraham Lincoln — a biography inevitably linked, as is all of American history, to slavery in the United States — when my older children were quite small, because I realized that I had never uttered the word “slavery” to them and worried in my own priveleged way about the anxiety it might produce in them. The fact that I feared anxiety or discomfort or, frankly, an awkwardness in explaining such important historical truths to a small child, rather than seeing it first and foremost as a way to talk about realities of suffering and injustice that permeates every experience in this country, was my and many other [let’s face it, “white”] parents’ first mistake. Now, when my child reads things that may in fact even cater to older, traditional ideas of gender roles, racial stereotypes, or other outdated ideals (not only James Bond, but how about Greek myths?!), I try to take the opportunity to talk about the past, the present, and the future… and how many authors often viewed their characters or subjects in ghastly or well-worn ways. When librarians or teachers or parents or the community at large say that something is inappropriate, especially when it comes to race, or gender/sexual identity, or poverty, or violence inflicted on the powerless, what is essentially being said is that someone who identifies with those stories is “inappropriate” as well. As Lisa Weinbaum says in the closing of her post,

Some may be unsettled by what we read in class, but as a principal once stated when discussing the Holocaust, “turning ours heads from it doesn’t make it go away.” And so I won’t turn my students away from stories that matter. And I won’t allow students to turn away from each other, either.

And as adults continue to embrace childish things, let’s not forget, our children are minutes away from adulthood, and it is our job to help them on their journey. Great literature for young and old from all corners of the world and the conversations it provokes…I’d say that’s about the best GPS there is.